INTERVIEW/

Osian Efnisien:

PROPAGANDA AND TINYISM

Brought up high amongst the pristine glaciers of Snowdonia, North Wales, young Osian found himself snowed in for six months of each year, spending the dark and stormy winters in front of the fire drawing and listening to the gruesome Celtic legends of his forebears.

We talked to him about fake advertising campaigns, fragile character patterns and his ongoing quest in search for new shapes and sizes…

Pictoplasma: Your characters are rather generic. You seem not to care too much about inventing something new, as you do about echoing forms that are part of our cultural subconscious. Can you still identify what you are referring to? How relevant are these references?

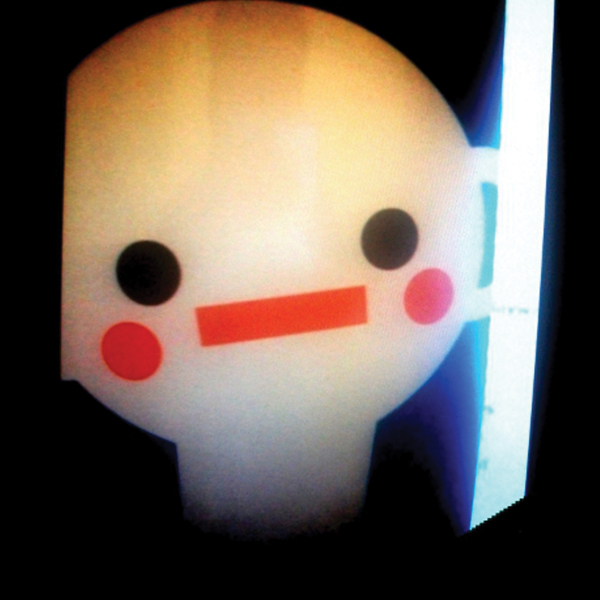

Osian Efnisien: My characters conform to certain archetypes, much in the way that children\’s drawings tend to depict buildings, people or animals in very stylised ways, uncluttered by the baggage of associations and misconceptions that we pick up as we grow into adulthood. I try to approach my work in that same manner. I draw my characters so that they spill out onto the page very quickly, so that they don\’t spend a lot of time “in my mind”. Sometimes, when I\’m drawing, I catch a glimpse of a character or a symbol that I recognise and I bring it out a little. So, the references to existing forms are there, but they always arise “after the fact”, rather than being consciously placed there for any particular purpose. This juxtaposition between the haphazard “chance” element and the more planned “rational” components of my work is very important in my creative process. It\’s about giving expression to the subconscious—to whatever degree that’s possible.

Pictoplasma: You don’t work primarily with digital media. What is the digital component of your work? Does it make sense to think of your work in terms of sampling and remixing, or is referencing and quoting more appropriate?

Osian Efnisien: My drawn characters are “analogue” versions of digital precursors. They all started as very basic geometric shapes, circles and triangles, with little faces and ears. They were all made using digital media, so my work could not have existed in the form it does now in predigital times. The technology allowed me to glimpse an economy of design that I would have been hard pressed to achieve otherwise.

I still use digital media as a design tool, arranging compositions and playing with colour.

I also chop up and splice characters together, swapping heads and bodies and faces, as well as importing characters from older drawings and from a large backlog of work that I have stored on disk. When this is all done, I trace the finished composition onto a piece of paper using a light box that I made from an old flat screen monitor and bits of wood banged together. So, although the end pieces are often hand-drawn, I would be perfectly comfortable being referred to as a digital artist—although “digital/analogue hybrid” might be a more precise description of what I do.

Pictoplasma: You started off playing with the mechanisms of advertising, running what you called mini-campaigns, distributing stickers, putting up posters on the street, and using commercial slogans that didn’t have products behind them.

Osian Efnisien: Rather than a commentary on advertising itself, the mini-campaigns were a comment on people’s indifference towards the imagery surrounding them. Usually they take the form of posters for public health and safety, fake political parties or corporations and so forth. I make up a spurious slogan or health warning, something like “Do not punch children in the face”, and would translate it into a foreign language; Russian for example. That way, I deliberately severed the link between text and image, between viewer and message, reducing it to little more than a disembodied image, devoid of purpose: just visual noise. It was about drawing attention to the sometimes absurd divergence between the aims and messages of traditional advertising, and the visual language which it employs.

Pictoplasma: Another recent concept of yours is “tinyism”, which could be translated as the unconsciousness of life forms about their own status. Does tinyism apply to humans too, or have they evolved beyond it? And what about characters?

Osian Efnisien: I’m a great believer in humanity. Human consciousness is the only force we know of, at the moment that can counter the entropy which surrounds us in the universe in any meaningful way. The concept of consciousness intrigues me, especially the thought that consciousness arises from inanimate matter, that billions of years of atomic, chemical and biological processes produced a mind capable of comprehending itself and the cosmos that surround it. We are born into this world as a raw product of the universe, as pure unformed thought, and as we grow up our thoughts are shaped by the societies we live in and we lose the elemental status that animals hold onto to a greater degree. Tinyism is my attempt to claw back and express some of that primordial consciousness, through the tiny mind.

Originally published in the “White Noise” catalogue accompanying the Pictoplasma exhibition at La Casa Encendida, Madrid, 2013