INTERVIEW/

Luke Pearson:

Life without Hilda

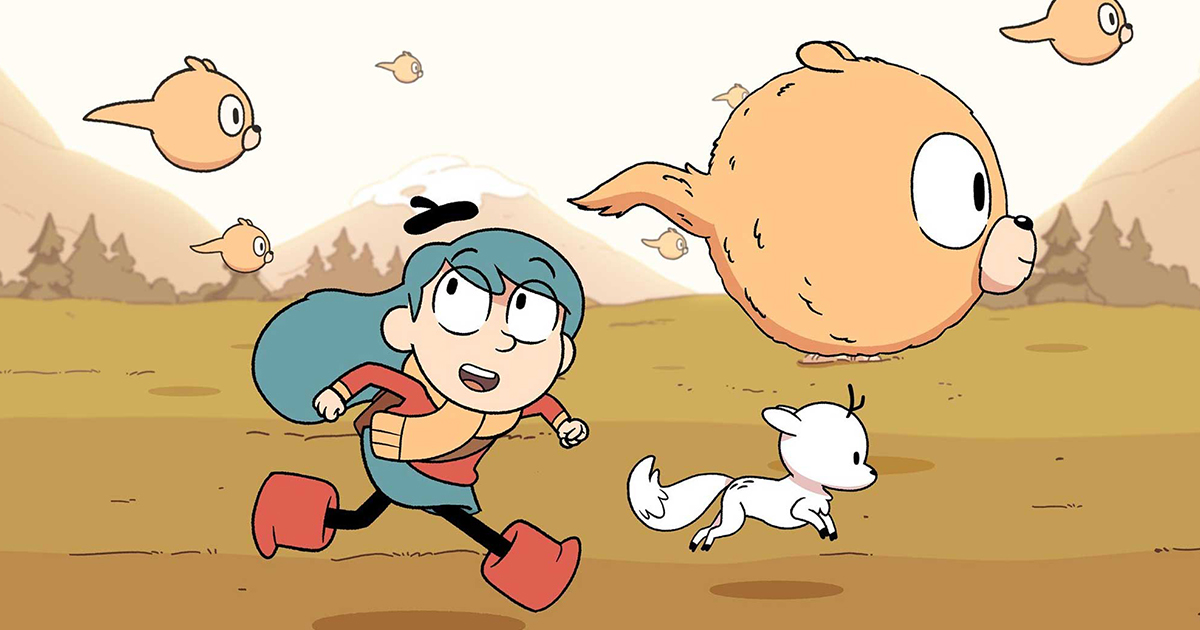

Nottingham-based illustrator and comic book artist Luke Pearson is best known as the creator of the ‘Hilda’ graphic novel series—and for the Netflix animated series based on them. Unbeknown to most people, he has worked as a storyboard artist on ‘Adventure Time,’ creates stop-trick animations with his partner Philippa Rice, and used to draw comics that had nothing to do with ‘Hilda.’ Shortly before publicly announcing the discontinuation of the series we met him at his Pictoplasma exhibition to talk about the genesis of his graphic novel, the intimidating move from the books to an international TV series, and the different levels of scariness in both media.

Pictoplasma: Your exhibition is all about Hilda.

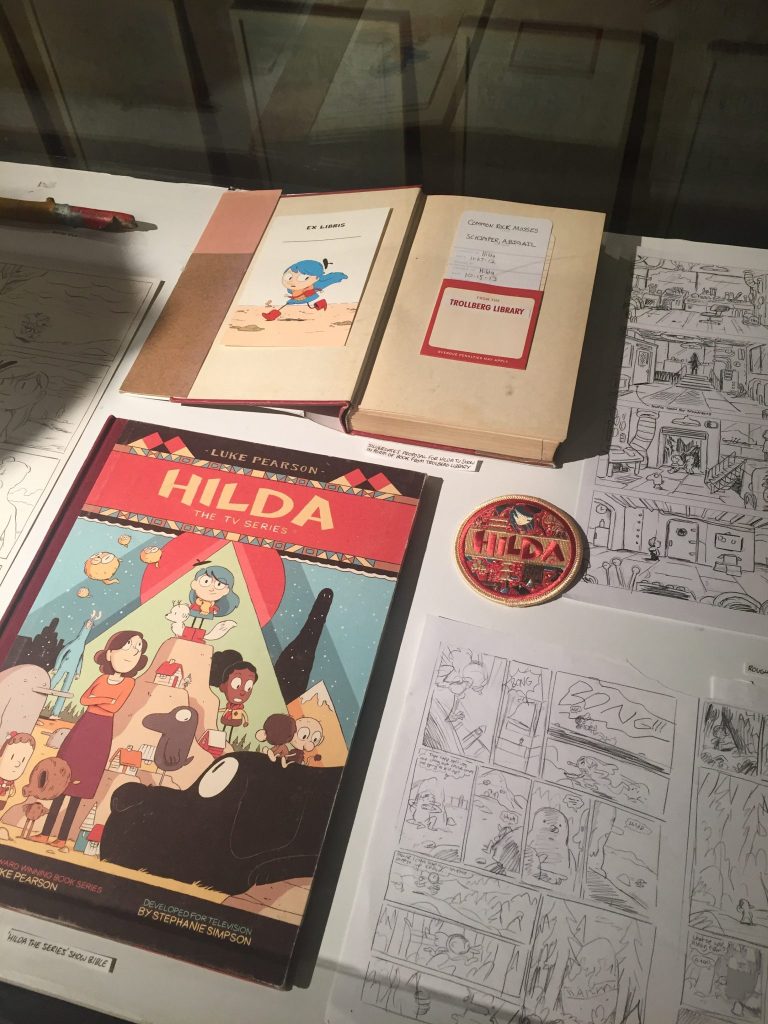

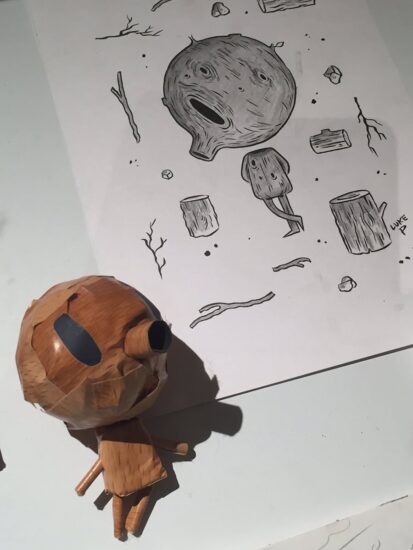

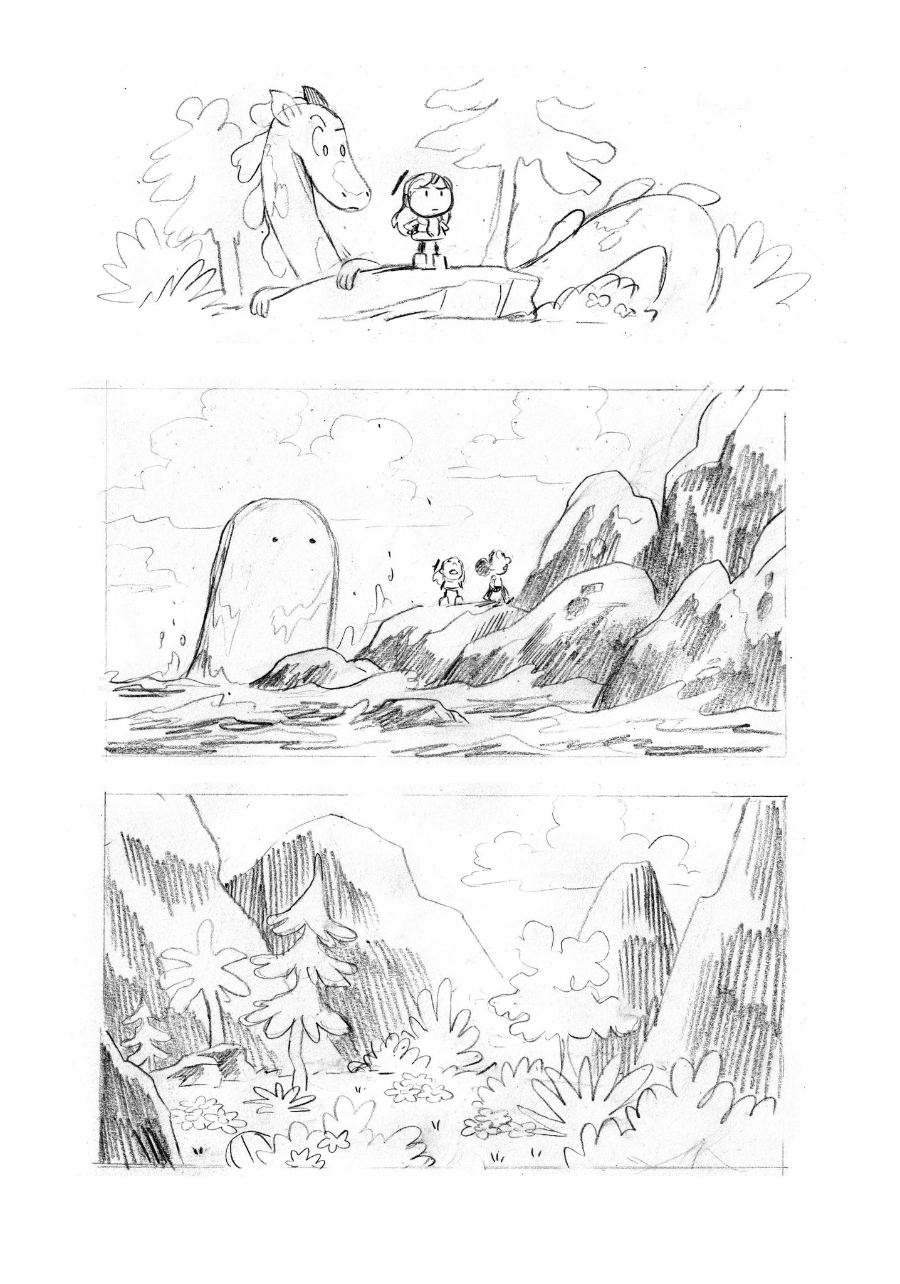

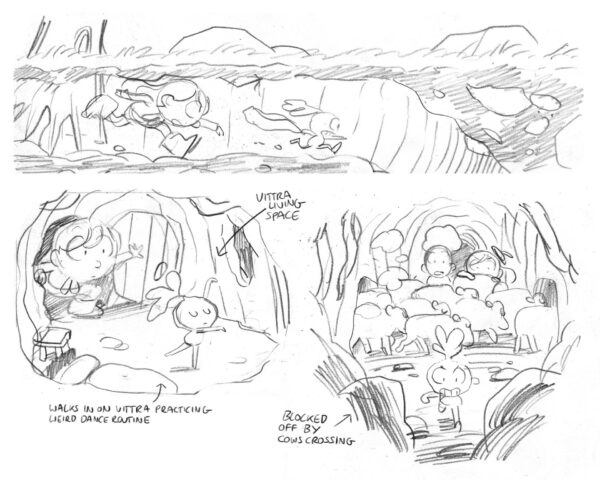

Luke Pearson: Yes, I’ve done very little else especially since my daughter was born two years ago. So I brought a selection of original pages from my Hilda series. On one wall I’m showing a page from each of the first four comics, on the other wall you see a few pages from the new comic that is coming out soon. I also brought a selection of artifacts from the history of Hilda. It starts with an old book on Scandinavian folklore that was the initial inspiration for some of my characters, and I’ve included some of my early sketchbooks, as well as several bits and bobs that lead right up to the animated series.

The book of Scandinavian folklore is opened in a two-page spread about a woodman that looks very similar to your character in Hilda.

Yes, that’s where the idea for my wooden character came from. The book is really good: it’s full of strange Scandinavian tales that were collected in the field back in the nineteenth century. They are not told very dramatically, more in a matter of fact kind of way, as if these creatures and events were real. That was part of what I wanted to capture with the first Hilda comic: the sense that all these magical things inhabiting Hilda’s world are no big discovery when she stumbles upon them. They’re fairly commonplace and she takes it all in her stride. Hilda’s woodman specifically came from this one very short story, though the character in it is a normal woodman and isn’t made of wood. I liked the idea of him bringing wood into her house and just lying down in front of the fireplace.

“There’s already plenty of fantasy fiction about elves and trolls out there, but there was a different, more mature feeling I got from reading theses old stories—a particular, quiet weirdness—that I wanted to transform into an accessible children’s adventure.”

When did you start researching Scandinavian folklore?

I found a book in the library at my university. We were doing a project on maps and I was assigned to do an illustrated map of Iceland. I wanted to pick something specific about the place—not just draw a literal map—so I made a folklore map. I researched different stories and legends from the area and tried to pin them to specific locations of the country. That’s how I got introduced to a lot of stories about belief in elves…

And you were hooked?

Yes, I kept reading these stories and it really sparked my imagination. So I took elements from that and melded it with stuff I invented myself, wanting to capture the feeling of that particular landscape in a fantastical way I hadn’t quite seen before. There’s already plenty of fantasy fiction about elves and trolls out there, but there was a different, more mature feeling I got from reading theses old stories—a particular, quiet weirdness—that I wanted to transform into an accessible children’s adventure.

While Hilda never seems to be afraid or even surprised by all the fantastical creatures she meets in nature, once she moves to the town she has real difficulties coping with the other children.

After a couple of books, as I started to think about Hilda as a longer series, I realized that there was only so much I was interested in doing with a character that never is afraid. It seemed more interesting to me to relocate her to a place where she would still have access to all the fantasy elements, but also be able to experience things that are more relatable to a kid in everyday life.

Was Hilda inspired by a real person?

Not really. She’s really more like a positive force. Someone you’d enjoy spending time with and follow on adventures. Sometimes I say she is the kid I wished I could’ve been—I think she’s the sort of person a lot of people would want to be.

A role model?

Yes. I’d like to think so.

“On the one hand it was very exciting, but I was also prepared that it might go in a direction that wasn’t what I wanted.”

You were involved in the series as a style and design consultant. But you weren’t hired as a character designer.

There was a whole team of people working on that full time. I did some initial storyboarding and wanted to do more, but it just wasn’t realistic. It’s so time consuming. In the end, I would just look at every element of the show as it came in and give them ideas. I wrote a few scripts. I was very hands on, and still am, overseeing the project as a whole.

Were you afraid you would feel alienated by the animated adaptation of your books?

Yes. On the one hand it was very exciting, but I was also prepared that it might go in a direction that wasn’t what I wanted. Happily, it turned out pretty much exactly as I would have wished. Naturally, it’s a collaborative process and lots of other people are involved in making decisions. I’ve accepted that it’s a group project now. My books are my books and the series is the series.

Would you agree that the books are a bit darker and scarier than the series?

Well, some stuff in the books might be a bit weirder, but the series is quite scary in its own way. There’s a character in the series called the Rat King, which was an old idea I’d had in mind for the original comics. Back then I felt it was too gross and scary for the books, so I boiled it down to a milder joke version in “Hilda and the Bird Parade,” where she thinks there’s a large rat king going around the corner, but it turns out just to be a little bundle of three mice tied together. In the series, we ended up turning that into a huge terrifying pile of rats. I think it’s quite scary.

“Hilda has an impact on my life in the sense that it’s the main thing I do, and I’m thinking about her every day.”

Moving images in general may be scarier for kids.

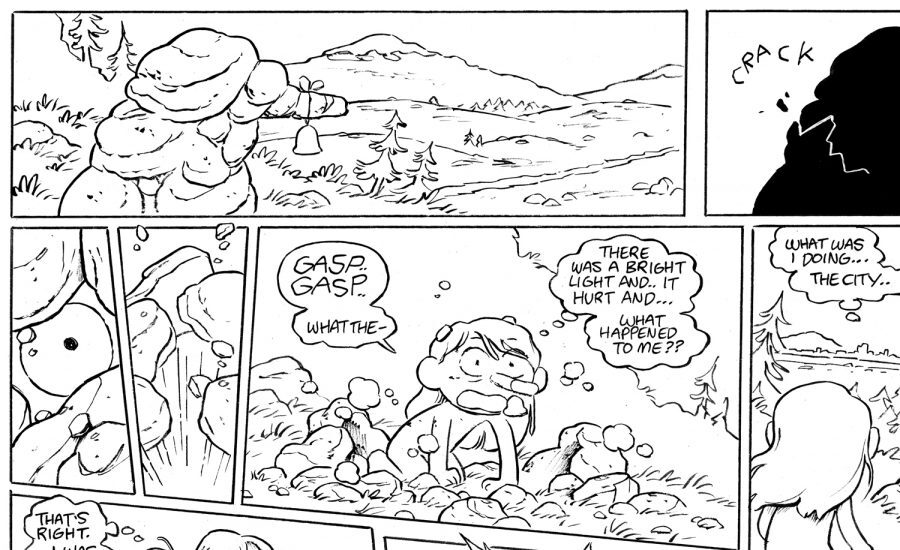

There’s a lot more sensory input than you get from looking at pages in a book: sounds, movement, cuts, and the lighting is far more immersive, so there’s more of a sense of being in there when you’re watching the show. Still, it really depends on how your imagination works. When I look at a comic, I’m quite detached. I’m looking at the artwork, thinking about how the panels are laid out and the quality of the writing. But when you’re a kid, you’re actually in the picture, you’re not thinking about who made it or how it was made, you’re just in there and taking it all at face value. It feels more real.

Your daughter is still too young to read herself. How does she react when you read it to her?

I haven’t yet, at least not properly. She sometimes pulls a copy of the book off my bookshelf. For some reason, the copy in the living room is a Finnish edition. I can’t read it myself. She pulls it out and just flicks through the pages and sort of reads it to herself. I’ve never tried to read a comic to her yet, but she is interested, she knows who Hilda is, she sees me drawing her. Soon I will sit down and try to read it to her, but for now she generally prefers books with a couple of sentences per page, not thirty speech bubbles.

The series is very successful. How has it impacted your life?

It’s good, I’m happy. Hilda has an impact on my life in the sense that it’s the main thing I do, and I’m thinking about her every day. Life would be very different without Hilda and I’m sure my career path would have been somewhat different if she hadn’t taken off early on.

Interview by Elise Graton on the occasion of the 15th anniversary edition of Pictoplasma Berlin, 2019