ESSAY/

Brian Duffy:

THE HUMAN MACHINE

Brian Duffy is a researcher in the field of social humanoid machines. His research has evolved from expert system technology for control in industrial manufacturing, through building autonomous artificially intelligence robots, to his current work on social humanoid machines. The challenges, consequences, and subsequent responsibilities of working in this field are his continuous source of motivation. He is currently a Senior Associate Researcher at the Smartlab Digital Media Institute, University of East London, UK.

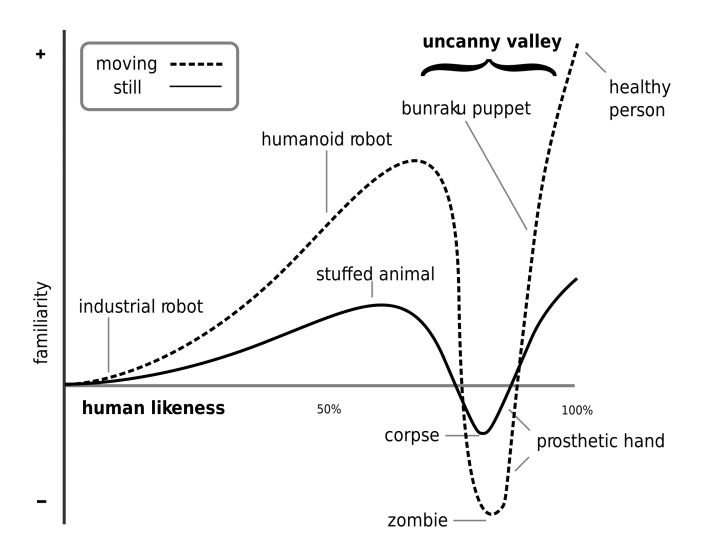

For Pictoplasma, he discusses the validity of the concept of the Uncanny Valley. Conceived in 1970 in the fields of robotics, it offers a model to explain human attraction and repulsion to machines and artificial life. It has been influential especially for humanoid robotics, but also animation film and its hyperreal aesthetics.

Humanity was forced to reassess its assumptions about technology during the Industrial Revolution, when through their role as a tool machines developed from enhancing human abilities to exceeding and ultimately replacing them (see Jacquard’s mechanical loom of 1801, and the subsequent growth of the Luddite movement). The ensuing riots testified to the impact technology regularly has on our way of life. Building an artificial human can therefore be seen to embody the biggest challenge that technology poses to humanity.

Whether it is our fascination with understanding the human body and its ‘control’ through medicine, or the holy grail of roboticists to replicate life in the form of a humanoid robot, the core theme is our search to understand and ultimately control what it is to be human. This article discusses the second aspect, our fascination with creating an artificial ‘living’ entity in the form of an autonomous social humanoid. With the current development of the social robot, incorporating such concepts as artificial intelligence, the humanoid form, and digital emotions, we are entering a new era of questioning what it fundamentally means to be human. Science and technology is dissecting our very being and trying to reproduce it in the form of a mechanistic artefact.

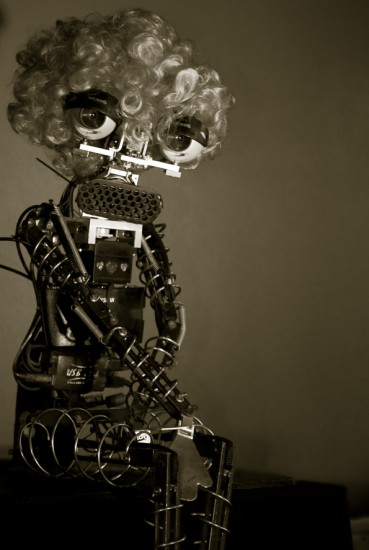

Many storytellers, from ancient times through Karl Kapec’s Robota play in 1923 to modern films or books such as Bicentennial Man or I, Robot, come from this perspective of digitizing the human. It involves the notion of decomposing the human into a mechanistic device with motors, sensors, a form of mechanical/computer brain, and housing all this in a representation of the human form. The anthropomorphic form is derived an assemblage of components. It starts to move, talk, and become artificially alive.

The Uncanny Valley constitutes a region along the anthropomorphic continuum where, as such a device becomes more and more human-like, our acceptance of it increases to a point where it suddenly fails. Something is just not quite right. It is judging according to it being human and failing, rather than being a device with some human-like characteristics with which we could sympathise. When assessed according to the human frame of reference, being too close is not enough.

There is considerable resistance to the notion of the Uncanny Valley amongst roboticists, whose arguments against it cite a lack of scientific evidence. Curiously, this is the very key as to why the term ‘uncanny’ is so appropriate. It involves an uncomfortable feeling that is often difficult to describe, yet relatively easy to replicate (recent computer animation of very human-like characters provides many examples that do not work well). Numerous experiments have tried to evaluate and ‘prove’ this theory so as to make it more palatable to the scientific mind, but either way there is an obvious reason why we are repulsed by very human-like, but not alive, artefacts. We distance ourselves from death (and that is the reason why horror films work so well).

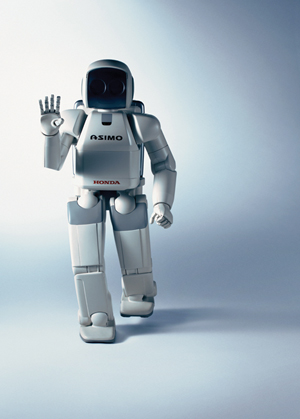

The humanoid form in robotics creates expectations about its physical and social behaviours that become more and more difficult to manage with increasing anthropomorphic resolution. It requires a balance between perceived and actual capabilities. If roboticists successfully achieve this necessary balance (or tilt it in favour of actual capabilities over those perceived), then their acceptance can be more successfully managed. So that expectations and actual capabilities can be controlled, Honda’s Asimo robots, for example, are demonstrated only in very controlled environments. In humanoids, two diametric opposites, the machine and the human, are being forced to meet with the Uncanny Valley fundamentally separating them. It provides a necessary barrier between human-like machines and artificial humans.

Many arguments have been made for building human-like machines, some with a certain degree of justification, many without. On reviewing the successful use of robotics to date (excluding short-term novelties), we see that industrial robots, for example, have little to do with the human form. But nor does a household washing machine: for the simple reason that it is necessary to optimize the machine for a specific task. The wish to generalize the role of the machine brings in the human as the obvious frame of reference for multi-functionality. While the human can be a valid source of inspiration for robot design, economics clearly dictates that a specialized device (often consumable) is a better choice than a significantly more expensive multi-purpose machine.

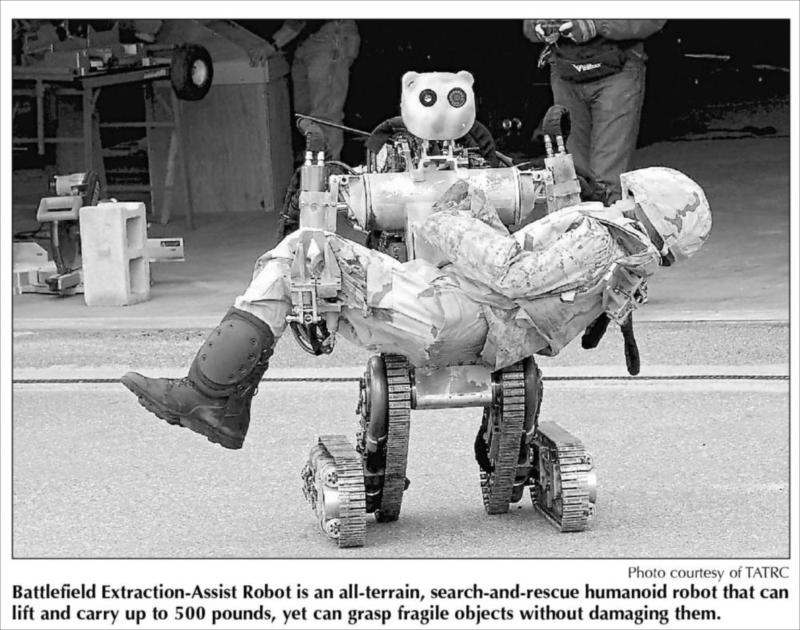

Other pro-anthropomorphic arguments are based on the machine being able to directly replace us in particular situations, having human-like dexterity, or being adapted to exist in our human-centric environment. Frankly, the majority of these justifications are inadequate. The direct replacement of humans in medical care for the elderly, for example, is absconding from our responsibilities as humans. Building machines with the same dexterity as humans should not be the objective, either, since it amounts to a constraint. We should build machines that have more degrees of freedom than we do, and are subsequently useful for purposes other than replacing us in tasks and roles based on what it fundamentally means to be human. The digital camera has the capability of viewing beyond our visible spectrum, motors are stronger than our muscles, and while it is argued that the capacity of our brains is phenomenal, computational devices can beat us on many levels and are evolving fast. It is the common direct comparison that is both inappropriate and incorrect.

Situations in which we are required to directly interact with machines introduce an additional perspective. Here, the engineer/designer is forced to consider what can facilitate and, just as importantly, not complicate the interaction. It is very tempting to introduce impressive aesthetics and build very human-like heads and bodies, based on the assumption that this will facilitate human-machine interaction. This assumption proves false in reality, and is basically the problem of managing expectations and obtaining the direct mapping between the exact role of the machine and the mechanisms which are used to realize it. A simple, well-designed touchscreen device can be a much more effective and efficient human-machine interface. This balancing of form and function, without succumbing to the temptation of over-engineering the interface, leaves, in fact, little justification for using a humanoid for human-machine interaction. If human qualities are necessary, then that is specifically why a machine is inappropriate, no matter how human-like it may appear. If human qualities are not necessary, then using machines to replace people can free us from tedious tasks.

The sensationalist negative aspects of robotics are numerous: machines taking our jobs, unethical, invading our privacy, emotional manipulation, humanity challenged, cold killing machines, robots will take over the world, return of the concept of slavery. The reality is that robots will develop, evolve, and ultimately ‘by-pass’ us, in a different direction. Machines have already done so in many specific contexts in which there is a successful balance between function and form. This is not something to fear. They are and will be something simply very different from us, which is precisely why robotics has such an interesting and promising future.

While the Uncanny Valley is a valid concept, it should not influence whether we should build humanoid machines or not. Overcoming the Uncanny Valley and invariably cheating us aesthetically and functionally is merely a question of resolution and technology, and will result in a great ‘demo’. But, as with any successful design, when we strive for a coherent balance between function and form, taking into account the exploitation of those mechanical and computational properties that make up the machine, successful artefacts will not be a humanoid. On the other hand, the trudging washing machine does not make us dream.

A useful outcome from the inevitable development of humanoid robotics (whether justified or not) will be the highlighting of what it is to be human. While endeavours to digitize the human should clarify those core features that make us human and combat our desire to rationalize humanity down to a collection of bits, scientists will continue to chase after the ghost within.

Originally published in Prepare for Pictopia, 2009