INTERVIEW/

Fons Schiedon:

A Monkey with an Oversized Head Raging and Screaming

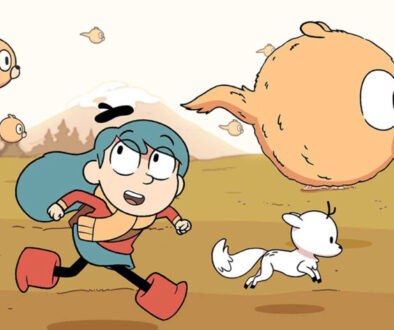

Dutch artist Fons Schiedon works as animation director and illustrator in New York. He has made a name for himself with his commercial, style-defining animation shorts and the chewing-gum-like distortion of his characters\’ body parts in time and space. All his work has a strong conceptual approach.

This interview was led in 2006, after Fons had his international breakthrough with a highly-respected campaign for MTV Asia and Motorola. Since then, his career took many surprising turns…

Pictoplasma: Over the past few years your work has undergone a change from a rather classical, illustrative and decorative style to more abstract, deconstructed and character-based work. Yet it is still surprisingly decorative. How does one work or job lead to the next?

Fons Schiedon: Illustration is just something I do as a way to communicate, but I have more of a passion for graphic design and film. For me it always has two sides: I love to tell stories but I personally enjoy watching something that’s less explicit.

Most of my work is client work. That and an expanding range of jobs have had a huge influence on what I do. I started off mainly doing magazine illustration. Animation was a much smaller part of my work, more a secondary thing. And then, almost by accident, I got to work on a documentary and did several smaller jobs in video and animation. All of a sudden that became the main thing. At the same time I was asked to collaborate on interior design projects—something completely different. The diversity and characteristics of the projects demanded a variety of approaches, so I had the opportunity to take directions that I had always been interested in but couldn’t really call upon while doing illustration.

The thing about influences is that jobs always come at the same time. I have worked on designs for interiors and animated idents for TV on the same day. In a situation like that—which I love—one thing affects another, obviously. I wouldn’t say that influence is so much a concept or style thing, because those elements are much too grounded in the basics of a job. It happens more on an abstract level. It’s a learning process where finding the solution to one problem makes it easier to solve another problem.

And then another aspect is the counter effect of working on certain projects. After spending several months doing stuff for preteens, I have to compensate by working on some adult-oriented work, just to keep the balance right. This also goes for character work. I love how character work is not restricted to any specific demographic—but even then, every once in a while I need something…well, you know, serious. So I have my literature illustrations and identity work that keep my brain from deforming into a cute mushroom cloud.

Pictoplasma: Do you feel a responsibility for your creations? Why do you expose them to so much violence?

Fons Schiedon: It’s even worse than that. They were made with the sole purpose of being exposed to violence, some of them at least.

These characters are all here for a reason. If it weren’t for the stories, they wouldn’t be here—because I wouldn’t have designed them. I’m a typical designer—not an artist, so the emotional connection you’re referring to is not too strong.

If anything, I feel a responsibility for the character’s integrity. They need a personality that makes them unique and enables them to behave differently from one another. You have to make these kinds of judgments when you’re doing a series: What is the character’s range? Would he do this or that? Is he kind to animals or not? Does he take out the garbage himself, or does he leave it to his retarded brother? Important questions to ask.

Pictoplasma: Characters such as Monki, Bad Boy Lense Flare or Squirrel have gained international recognition value. Are there any plans to draw on the hype and push them into the third dimension as designer toys and urban vinyl collectables?

There are no plans in the works, but I could imagine they would work as vinyl toys. It will be different—but I actually think they could gain something. A contortionist like the Bad Boy would make for a great 3-D shape.

There are no plans in the works, but I could imagine they would work as vinyl toys. It will be different—but I actually think they could gain something. A contortionist like the Bad Boy would make for a great 3-D shape.

But I also like the idea of a more low-cost range: toys that you can actually play with and give away as a present, as opposed to overpriced vinyl collections.

Pictoplasma: Monki especially is a perversion of childlike characteristics, a common container for all kinds of content that is currently being targeted at an adult generation. Do you consider your work to be part of a larger movement?

Fons Schiedon: We have access to the most perverted content, if we want to see it. If there ever were a time where the complex range of human desires is so clearly visible, it would be today. If I want to see a guy being hit dead by a truck, I can. I can find videos of people inserting the most unbelievable objects in themselves. I just need to decide whether I want to see that, or if I think it crosses a line.

If I did something like that with characters, it wouldn’t be fun. You’d think that it’s over-the-top. There is animated content like that, and it’s boring and disgusting because it crosses a line of what we can think of as being funny. All I do is tease…brush up against a border every once in a while, but it’s all within the safety zone of TV regulations (and my own standards). I wouldn’t be interested in taking it further than this. I mean, really, it’s not edgy.

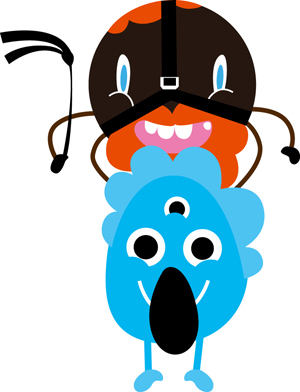

The reason why Monki or others contain these references to adult behavior is because they’re targeted at an adult or teenage audience. Viewers have to be able to identify with a character. Appeal is the most important thing. That’s true for actors in film, and it goes for actors in animation too.

You know, I have done idents such as a panda in a tutu. It\’s funny, sure—but personally I don\’t get anything out of watching that kind of thing. It’s not for adults. But a monkey with an oversized head raging and screaming—how can that not work? We all understand how that feels.

Pictoplasma: You combine plain cuteness with blunt violence, stylised innocence with hyper sexuality and naive sympathy seekers with painful disabilities… Would you describe your spin on character design as typically male?

Fons Schiedon: No. I would describe it as typically human. I don’t believe in character design that is single-sided. It’s not natural. Simple things only happen on preschool TV. After the age of two we become interested in layering, in how something can appear differently than it is, or how it can take different shapes. When I do characters, I’m looking for something interesting, something that gives them reasons and motivations: a personality. Often they only have as much personality as is shown on screen (the part that is not shown is simply not constructed), because I don’t sit down to write them a full biography. In many cases the personality will only take shape as the story is written. Often when working with groups of characters (which I usually do), it’s important to get the group dynamic right. Visually you have to find a good balance in proportions; in animation timing you should give all characters a pace of their own and a different range of expressions. If you look at the monkey, it’s a character that is tailored to have big expressions with his enormous head and oversized eyes. The koala hardly has any means of expressing himself—so his movements are much smaller and less dynamic and he does nothing with his face. Monkey and Koala are a good couple. If you bring in a large bear that is somewhere in the middle in terms of his range but has a strong presence because of his size…then you have a group that works on screen.

Pictoplasma: What was the best time of your life so far: being a child, a teenager or a twen?

Fons Schiedon: Now is a good time.

Originally published in The Character Encyclopaedia, 2006